Planning Resilient University Town

Purpose of the Handbook

The handbook is designed as a resource for UCA leadership, local government authorities, community members, and institutional partners, offering insights and best practices for fostering vibrant university towns. It will highlight UCA’s impact and provide direction on creating an enabling environment where universities serve as drivers of urban innovation, environmental sustainability, economic development, and cultural enrichment.

The concept of university town development was envisioned by UCA’s founding Chancellor as a core pillar of UCA’s long-term strategy, ensuring that its campuses act as catalysts for regional transformation. By fostering a collaborative approach, this initiative seeks to align the efforts of UCA and local stakeholders in strategically planning, co-developing, and strengthening the towns in which the University is located.

PART I

In the context of current challenges such as climate change, economic uncertainty, and other global shocks, it is becoming increasingly urgent to reconsider the role of educational institutions in strengthening resilience capacities. Notably, the sustainable development of Central Asian Mountain towns, often characterised by geographic isolation, environmental vulnerability, and socioeconomic challenges, requires universities to take on new roles to achieve sustainable urban development. Historically, universities have evolved from being centres of higher learning to dynamic drivers of local, regional and international development. Starting in the late 20th century, universities were increasingly seen—and saw themselves—as catalysts for knowledge-based economic growth, responding to de-industrialisation by generating innovation, technology, and human capital. The shift in universities' role marked the beginning of a new era in which academic institutions became critical actors in the global movement toward the knowledge economy and drove innovation.

Central Asian universities are in transition, and it is unclear if they can become a transformative engine that can profoundly shape the economic, cultural, and social landscape of their hosting cities and towns. Scholars argue that developing countries should aim for "developmental universities" to contribute to social and economic development (Brundenius et al., 2009) Universities should promote problem-oriented research and education relevant to local needs and foster interactive capabilities to engage with various societal and industrial actors. Therefore, this handbook aims to cover this gap based on the hypothesis that the University of Central Asia’s experience can be a solid basis for devising a workable concept of a resilient university town, integrating academic expertise with local knowledge, fostering innovation tailored to regional needs, and actively contributing to sustainable development.

List of references

Brundenius, C., Lundvall, B. Å., & Sutz, J. (2009). The role of universities in innovation systems in developing countries: developmental university systems–empirical, analytical and normative perspectives. In Handbook of innovation systems and developing countries. Edward Elgar Publishing.

In the context of post-Soviet industrial towns, educational institutions may serve as stabilising anchors in economic decline, providing education and acting as major employers to replace collapsed traditional industries. However, it is essential to distinguish the concept of “university town” discussed in the handbook from the Soviet concept of “naukograd” or “akademgorodok”. Akademgorodok near Novosibirsk, Dubna near Moscow, Arzamas-16 (now Sarov), and Krasnoyarsk-26 (now Zheleznogorsk) were deeply influenced by Soviet-era policies, where higher education was highly centralised and aligned with the Soviet government’s goals. Naukograds were developed to advance strategic scientific research, often in isolation, focusing on maintaining secrecy and security. They specialised primarily in nuclear energy, weapons development, and aerospace, serving as critical hubs for state-directed innovation. While Soviet “naukograd” or “akademgorodok” and Western “university towns” share the common goal of advancing knowledge and innovation, their governance models, purpose, and integration with local communities set them apart. Naukograds, born out of the Soviet need for strategic scientific advances, were isolated and controlled by the Soviet government.

Table 1. The main difference between Western and Soviet university towns

|

Characteristic |

Western University Towns |

Soviet Naukograds (Akademgorodok) |

|

Governance Model |

Decentralized, with autonomy in academic and research activities. |

Centralized, controlled research aligned with government priorities. |

|

Integration with the Economy |

Integrated with the market economy, fostering private sector partnerships and entrepreneurship. |

Driven by a planned economy, research focused on government-directed innovation. |

|

Funding Sources |

A mix of government funding, private sector partnerships, and tuition fees. |

Primarily government-funded, with limited or no private sector involvement. |

|

Innovation Approach |

Encourages interdisciplinary research, commercialisation of discoveries, and startup ecosystems. |

Focused on strategic government needs, with little emphasis on commercial applications. |

|

Sustainability |

Adapted to globalisation, fostering new forms of university-industry collaboration. |

Struggled to transition after the Soviet collapse, with some repurposed for modern research. |

Since the 1980s, globalisation and increased competition have pushed firms to seek external sources of innovation, resulting in a new form of university-industry collaboration in most US and Western European countries. On the one hand, declining profits and rising research costs encouraged firms to outsource more basic research to universities. On the other hand, financial constraints faced by universities led to the pursuit of new funding sources through partnerships with the private sector. Successful examples like MIT and Route 128, Stanford and Silicon Valley, and the Cambridge Phenomenon further demonstrated the transformative potential of these collaborations. To some extent, US military spending and defence contractors also added value in driving the growth of Silicon Valley engagement of universities like Stanford and UC Berkeley (Hershberg et al., 2007). However, unlike Soviet naukograds, US universities foster innovation through open collaboration and integration with the market economy, making them more adaptable to global research trends and economic needs.

After gaining independence, Central Asian countries have started selectively adopting Western models of university towns, mainly supporting the internationalisation of existing universities, primarily located in large cities. Located in the capital city of Kazakhstan, Nazarbayev University (NU) exemplifies the adaptation of the Western model, with significant funding from the national government institution to develop cutting-edge technical education aligned with global academic standards. Founded in 2010, NU is one of the leading research institutions in Central Asia, with 13.8% of its faculty publications ranking in the top 10% of most-cited globally. With 68% of faculty from 57 countries and partnerships with universities like UCL and Carnegie Mellon, NU follows an international governance model with courses taught in English. NU fosters renewable energy, biotechnology, and AI innovation through the Nazarbayev University Research and Innovation System.

While many Central Asian universities have sought to adopt the Western university model through internationalisation and academic partnerships, their direct contributions to local economic development remain limited. Even institutions such as Nazarbayev University, despite significant investments in research and innovation, have primarily contributed through knowledge generation rather than direct economic impact. Unlike most universities in Central Asia, which have yet to prioritise local economic development as a core mission, the University of Central Asia (UCA), with its 25-year history, stands out as a pioneering institution actively shaping its host towns' economic and social transformation. By embedding itself in its host towns' economic and social fabric, the UCA case can represent a unique model for university-led transformations in urban development in Central Asia.

List of references

[1] Hershberg, E., Nabeshima, K., & Yusuf, S. (2007). Opening the ivory tower to business: University–industry linkages and the development of knowledge-intensive clusters in Asian cities. World development, 35(6), 931-940.

The main achievement of top Western universities was that they could expand their societal role through broader forms of engagement, such as living laboratories and urban development co-planners. Through collaboration with residents, businesses and local governments, universities contribute to their towns' sustainable and resilient urban development, enhancing the quality of life and ensuring that urban transformations are driven by knowledge, innovation, and community well-being. As universities expand their local development roles, they are increasingly at the forefront of sustainability and climate action, leveraging their research capacity, infrastructure, and global networks to drive meaningful change. Leading institutions worldwide are committing to ambitious net-zero targets, integrating clean energy solutions, and developing innovative sustainability initiatives that extend beyond their campuses.

Many universities committed to net-zero carbon emissions are setting ambitious targets and implementing transformative projects to enhance energy efficiency. Cambridge University’s Cambridge Zero initiative leads the charge for net zero by 2038, integrating research and policy to reduce emissions across sectors. Princeton University has set its net-zero goal for 2046, already achieving a 33% reduction in emissions since 2008 through the Princeton Energy Plant. MIT’s Climate Action Plan aims for carbon neutrality by 2026, supported by renewable energy partnerships like its solar farm in North Carolina, which provides 40% of campus electricity. At Stanford, the Stanford Energy System Innovations project has reduced emissions by 68% and potable water use by 18%, demonstrating its strong commitment to sustainability. ETH Zurich targets net zero by 2030, combining initiatives like its Energy Hub and Zero Emission Campus Initiative. Tsinghua University, targeting carbon neutrality by 2050, supports this goal with sustainable campus efforts, including solar installations and energy-efficient buildings. Harvard is committed to becoming fossil fuel-free by 2050, contributing research on carbon storage through new forest management practices in collaboration with the state government of Massachusetts.

Universities are developing urban sustainability and resilience research hubs. Caltech’s Resnick Sustainability Institute advances research in climate science, clean energy, and sustainable infrastructure. At the same time, Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute and Oxford Programme for the Future of Cities focus on climate resilience, urban sustainability, and biodiversity. Cambridge’s Institute for Sustainability Leadership collaborates with over 1,000 organisations worldwide, driving global sustainability leadership through initiatives like the Prince of Wales’s Corporate Leaders Group. Stanford’s Urban Resilience Initiative works on climate adaptation strategies, collaborating with nearby cities like San Francisco. At the same time, Harvard’s Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability and the Harvard Climate Solutions Living Lab contribute to innovative climate solutions. Imperial College London’s Grantham Institute for Climate Change and Transition to Zero Pollution initiative focuses on climate resilience and pollution reduction.

Universities are implementing green campus initiatives and promoting sustainable building practices. Princeton’s LEED-certified Frick Chemistry Laboratory uses 30% less energy than comparable buildings. At the same time, the University of Toronto incorporates green infrastructure with LEED-certified buildings such as the Environmental Science and Chemistry Building. MIT’s MIT.nano project supports ultra-low energy consumption and sustainable materials in nanotechnology research. The Harvard Grid accelerates sustainability-focused technology development at Harvard, while Tsinghua University integrates sustainability through campus-wide solar panels, energy-efficient buildings, and water recycling.

Universities collaborate closely with policymakers and industries to address global sustainability. In collaboration with the Cambridge City Council, Cambridge University’s Cambridge City Centre Heat Network works to reduce carbon emissions in city buildings. Harvard partners with Boston’s Green Ribbon Commission and the Cambridge Compact for a Sustainable Future to enhance local resilience.[i] Imperial College’s Imperial Policy Forum connects researchers with policymakers to drive sustainability initiatives. Oxford collaborates with the Global Centre on Adaptation to support urban resilience and nature-based solutions. Stanford University works with local governments on projects like the Stanford Urban Resilience Initiative and supports city-wide climate adaptation strategies. Tsinghua’s Institute of Energy, Environment, and Economy plays a role in advancing China’s sustainable policy, supporting the national goal of carbon neutrality.

The University of Northern British Columbia played a key role in supporting community planning and sustainable diversification in Tumbler Ridge, a mining-dependent town in British Columbia (Darko & Halseth, 2023). Faced with economic volatility and boom-bust cycles due to reliance on coal, Tumbler Ridge aimed to overcome this path dependence by investing in place-based planning and sustainable development initiatives. In 2014, the university’s Community Development Institute partnered with Tumbler Ridge to develop a Sustainability Plan, guiding the town's transition from a single-industry economy to one with diverse economic foundations. Through this collaboration, the town leveraged UNBC’s research and expertise to support local infrastructure, tourism, and natural resource management, fostering a resilient, diversified community prepared to navigate the challenges of economic dependence on natural resources.

In summary, leading universities worldwide are increasingly becoming catalysts for sustainable urban development through research, green infrastructure, and collaborative governance. By adopting ambitious carbon neutrality goals, supporting sustainable urban planning, and engaging with local communities, institutions like Cambridge, Princeton, MIT, and several other have demonstrated their capacity to drive both environmental stewardship and economic resilience. Their success lies in leveraging interdisciplinary expertise and forming partnerships with policymakers, businesses, and citizens, thus aligning academic research with real-world sustainability challenges.

In contrast, universities in post-Soviet countries, while making progress toward sustainability, often face structural and institutional barriers that limit their broader societal impact. For example, Nazarbayev University’s Green Campus Initiative in Kazakhstan serves as a local model for waste reduction and energy efficiency. However, its influence on national policy and urban planning remains limited compared to its Western counterparts. Similarly, Skoltech’s focus on renewable energy and environmental technology is notable within Russia’s innovation ecosystem but faces challenges related to regulatory environments and limited industry-academia collaboration. Westminster International University is beginning to integrate sustainability principles into its curriculum in Uzbekistan. Additionally, it has demonstrated its commitment to environmental sustainability through initiatives like tree planting on campus and supporting the national "Yashil Makon" project. The American University of Central Asia in Kyrgyzstan emphasises environmental responsibility through energy-efficient campus design and sustainability education. However, broader engagement with local communities and governance structures remains nascent.

List of references

Darko, R., & Halseth, G. (2023). Mobilizing through local agency to support place-based economic transition: A case study of Tumbler Ridge, BC. The Extractive Industries and Society, 15, 101313.

In many communities, universities are the largest employers, driving local economic development by directing university contracts and purchases to nearby businesses. Oxford University is responsible for 17,000 jobs and injects £750 million annually into the local economy. Harvard University is the fifth-largest employer of Massachusetts residents and the largest in the City of Cambridge. It supports 50,000 jobs in the local and regional economy through direct and indirect employment, research, and business partnerships. MIT has helped launch over 30,000 companies, creating millions of jobs globally, with a focus on the Greater Boston and nearby Silicon Valley (Roberts & Eesley, 2011). Stanford University employs approximately 18,000 staff and faculty. In addition, 43,000 local jobs are attributed to Stanford's presence, both directly and indirectly, in the broader Bay Area. These examples illustrate universities' pivotal role in fostering job creation and business development.

The alignment between education and employment opportunities significantly influences the returns on investment in human capital. Regions with strong university-industry linkages tend to achieve better education-job matches, fostering economic growth and innovation (Iammarino & Marinelli, 2015). This dynamic is evident in leading universities worldwide, which serve as economic anchors in their regions. Entrepreneurs from the University of Toronto community have raised over $12 billion in funding and created over 17,000 jobs since 2020. The Technical University of Munich is pivotal in Bavaria’s economy, generating approximately 62,400 jobs and contributing an estimated €200 million in hypothetical tax revenue. ETH Zurich generates approximately USD 13 billion annually for Switzerland, supporting thousands of jobs and advancing research. These examples underscore the vital role of universities in strengthening local economies by aligning education with labour market demands.

List of references

Iammarino, S., & Marinelli, E. (2015). Education–Job (mis)match and interregional migration: Italian university graduates' transition to work. Regional Studies, 49(5), 866–882

Roberts, E. B., & Eesley, C. E. (2011). Entrepreneurial impact: The role of MIT. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 7(1–2), 1–149. https://doi.org/10.1561/0300000030

Modern universities now play a "third role," engaging in research and development, industry collaboration, and technology transfer to meet societal expectations and economic demands (Russell, 1993; Minshall, Druilhe, and Probert, 2004). In the USA, the effects of university-based knowledge or innovation are typically felt within a radius of about 75 miles from the university (Fritsch & Slavtchev, 2007). Stanford's ecosystem has created over 39,900 companies, collectively producing $2.7 trillion in annual revenue (Eesley & Miller, 2018). Stanford graduates have founded, built, or led thousands of businesses, including some of the world’s most recognised companies—Google, Nike, Cisco, Hewlett-Packard, Charles Schwab, Yahoo!, Gap, VMware, IDEO, Netflix, and Tesla. MIT alumni-founded companies generate $2 trillion in global revenue annually. Harvard supports over 1,500 startups, particularly in life sciences, through facilities like the Pagliuca Life Lab. Similarly, ETH Zurich has launched approximately 250 spin-offs over the past decade, with a notable increase in recent years. In 2023 alone, 43 spin-offs were established, particularly in artificial intelligence and biotechnology. In 2020, these spin-offs collectively raised over CHF 400 million (approximately USD 430 million) in venture capital With approximately 2,034 active U.S. patents and an average of 170 new patents issued annually, Caltech has fostered high-tech and biotech innovation through startups like Impinj. Tsinghua University drives innovation in AI and biotechnology through its Tsinghua x-lab incubator, supporting ventures like SenseTime, a global leader in AI.

In the current technological age, the value of university impact is often measured by the number of patents, licenses, and spin-out firms, which directly impacts a region's long-run economic development. Oxford University has spun out over 200 companies, raising £850 million in investments, particularly in biotechnology and AI. At the same time, Cambridge University’s commercialisation arm, Cambridge Enterprise, has created over 1,500 startups and holds over 1,000 patents. Universities like Princeton, Caltech, and Grenoble Alpes University each manage extensive patent portfolios, fuelling sectors from biotechnology to AI and supporting numerous startups that significantly impact their local economies and beyond. Breznitz (2014) emphasises that this success depends on the ability of the university to transfer knowledge into the public domain in conjunction with the ability of the region to absorb that information.

List of references

Breznitz, S. M. (2014). The fountain of knowledge: The role of universities in economic development. Stanford University Press.

Eesley, C. E., & Miller, W. F. (2018). Impact: Stanford University’s economic impact via innovation and entrepreneurship. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 14(2), 130–278. https://doi.org/10.1561/0300000074

Fritsch, M., & Slavtchev, V. (2007). Universities and innovation in space. Industry and innovation, 14(2), 201-218.

The University of Oxford has fostered strong relationships with industries through initiatives such as the Oxford University Innovation, which facilitates the commercialisation of academic research, leading to sectors like pharmaceuticals and medical technologies. The Technical University of Munich has developed effective linkages with the automotive and engineering sectors by working with industry giants like BMW and Siemens to conduct cutting-edge research and drive innovation, directly impacting the Bavarian economy. ETH Zurich is a prominent example of a collaboration between universities and industries in Switzerland. The university is deeply involved in partnerships with companies like ABB and Swiss Re to advance robotics, sustainability, and biotechnology research. ETH Zurich’s emphasis on technology transfer and innovation has contributed to the city's economic growth, particularly in industries like engineering, IT, and pharmaceuticals. Grenoble has become a European centre for microelectronics and nanotechnology, mainly due to the collaboration between Grenoble Alpes University and local industries, including global corporations like STMicroelectronics The city’s research parks and institutions have been key in fostering technological advancements and driving the regional economy.

Several factors make University-industry collaborations more likely to occur in some universities than others. The disciplines emphasised play a key role, with technological universities like MIT or the Politecnico of Milan and Turin leading innovation and industry partnerships. The academic culture of a university also matters, as institutions may prioritise different goals. For instance, in developed countries, entrepreneurial universities focus on market-oriented, short-term problem-solving within the industry. In contrast, in developing countries, developmental universities emphasise social and economic development rather than profit-making, maintaining autonomy while engaging with various societal groups. The university leadership also influences the extent of collaboration, with proactive strategies favouring partnerships. A university's development strategy is crucial, as seen in Finland, where research is aligned with regional needs, as in universities like Oulu and Eastern Finland. Lastly, the environment around the university—such as a thriving industrial sector or science parks like Research Triangle Park or Cambridge—facilitates stronger industry linkages. These factors shape how universities engage with industry and contribute to regional and national growth.

Some authors argue that universities with strong scientific bases should focus on forming a few high-quality partnerships with firms that can absorb and spread knowledge. For example, in Chile, research supports this hypothesis, with firms with more substantial knowledge bases showing a higher likelihood of engaging with universities and forming more selective and valuable partnerships (Iammarino & Marinelli, 2015). This was not the case in Italy, where even firms with weaker knowledge bases engaged in U-I linkages, leading to less productive outcomes, with informal collaborations often leading to dead ends, especially in clusters with weak firms. Following this reasoning, in developing countries, "weaker" universities should receive support to enhance their internal scientific capabilities rather than being pressured to act primarily as problem-solvers for industry.

Universities play a crucial role in shaping public policy by fostering evidence-based decision-making and engaging with national and local governments. Below are examples of the University of Oxford, Stanford University, the University of Tokyo, Tsinghua University, the University of Toronto, and the Technical University of Munich. These exemplify this impact through various initiatives that bridge academic research with policymaking. From advancing sustainable transportation and AI governance to advising on economic reform and disaster management, these universities contribute to policy innovation through interdisciplinary collaborations and strategic partnerships.

Oxford supports evidence-based policymaking via the Oxford Policy Engagement Network (OPEN) and Local Policy Lab, facilitating knowledge exchange and partnerships with policymakers. The recent projects of the Local Policy Lab initiative—a collaboration between Oxford University, Oxford Brookes University, and the County Council—ranged from promoting health through community gardening at NHS sites to mapping green space quality and decarbonising schools. A recent OPEN Seed Fund grant was awarded for collaborating with Oxfordshire policymakers to explore the viability of electric car clubs in rural areas by establishing 'park and charge' stations and trialling electric vehicle sharing. The trial's results will help policymakers assess whether electric car clubs can meet broader goals like reducing emissions, promoting social inclusion, and supporting sustainable transportation in smaller communities.

Stanford's Office of Government Affairs acts as a key liaison between the university and all levels of government on issues closely related to the university's core priorities: research, education, and healthcare. Stanford researchers maintain a strong collaborative relationship with government entities, exemplified recently by their involvement in the Joint California Summit on Generative AI, co-sponsored by the Stanford Institute for Human-Centred Artificial Intelligence, where California Governor Gavin Newsom and academic leaders convened to discuss the impact of AI technology. Stanford researchers were among the first recipients of the National AI Research Resource pilot program, a landmark federal initiative to enhance AI research infrastructure.

The University of Tokyo plays a central role in shaping public policy in Japan, primarily through its Policy Alternatives Research Institute (integrated with the Institute of Future Initiatives) and Graduate School of Public Policy. Faculty members frequently advise the Japanese government on significant issues such as climate change, economic reform, disaster management, and urban development. The University of Tokyo policy research has been instrumental in developing Japan’s national innovation strategies and guiding the government’s response to natural disasters, such as the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Tsinghua University guides significant national policies in technology development, environmental sustainability, and urban planning. Faculty from Tsinghua University plays a critical role in shaping China’s Five-Year Plans, contributing to sections that define the country’s economic and development priorities, such as clean energy advancements and innovative city initiatives.

The University of Toronto’s Urban Policy Lab partners with government agencies to address housing, transportation, and infrastructure issues. Notable projects include the Who Does What paper series with the Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance, which examines municipal roles in Canadian urban policy, and the Canadian Urban Policy Observatory proposal to centralise city data. Additional initiatives include the Canadian Municipal Barometer annual survey, the Council Scorecard for civic education, and the City Hall Task Force to improve Toronto’s City Council governance. The Technical University of Munich’s Think Tank provides policy recommendations for crises like COVID-19. The university also promotes public transport over cars through transport planning, establishing tangential transport connections and public transport routes.

Universities build trust-based partnerships with local governments, positioning themselves as key actors in addressing pressing urban development challenges. By leveraging research expertise and financial resources, universities contribute to urban transportation, housing, and sustainability policies. The partnerships of universities with municipal governments exemplify how universities play a strategic role in shaping urban policy and fostering sustainable urban development.

MIT collaborates with local governments on urban planning issues such as transportation, housing, and sustainability, shaping zoning and land-use policies. For example, MIT’s Senseable City Lab works with municipalities to develop data-driven solutions for urban mobility challenges. The lab has influenced transportation policies by providing insights into traffic management, ridesharing, autonomous vehicle deployment, and infrastructure planning. MIT has also partnered with the Massachusetts Department of Transportation on congestion pricing studies and the future of urban mobility.

Harvard University works with the City of Cambridge and Boston on sustainable development, transportation, and affordable housing initiatives, ensuring the university's involvement aligns with broader urban policy goals. Through nearly 180 unique projects, the university has contributed to financing over 7,000 affordable housing units in Boston and Cambridge. Since 2000, Harvard has invested $20 million in its revolving loan program, the Harvard Local Housing Collaborative, to increase affordable housing in these areas.

For decades, Princeton University has voluntarily contributed to the Municipality of Princeton. In January 2024, the University announced contributions of $50 million over five years to the municipality and community organisations, including supporting property tax relief for eligible low—and middle-income residents. The anticipated contributions include a total of $28.2 million over five years in unrestricted funding to the municipality and an additional $11.35 million to support specific projects related to mass transit, infrastructure repairs and improvements, acquisition of emergency equipment, costs related to fire department personnel, construction of municipal facilities, and emergency housing.

Universities can actively engage with local communities and stakeholders through various initiatives aimed at fostering collaboration and public involvement. Oxford University promotes public engagement through exhibitions, outreach programs, and educational activities, leveraging resources like the Botanic Garden, Museums, and the Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities to connect with the community. Stanford University facilitates community partnerships through its Office of Community Engagement, which collaborates with external groups to address shared challenges, and through development offices that engage alumni, parents, and friends in supporting the university’s mission. Harvard University collaborates with over 140 local nonprofits. It works closely with state agencies on public health, education, and sustainability projects, exemplified by initiatives like Project Teach and partnerships addressing food insecurity through Food for Free.

Many universities partner with local schools and organisations to improve STEM education. Caltech’s Community Science Academy, Imperial College Outreach program and ETH Youth Academy aim to promote STEM engagement in local schools, encouraging participation from young students and underrepresented groups and providing public lectures that foster community involvement. MIT contributes to the local community through STEM education for underserved students, the Public Service Center, and the CoLab, focusing on volunteerism and urban development projects in underserved areas. Tsinghua University supports financial literacy programs for Beijing residents, while Peking University Medical School and community health programs offer medical care and services.

Cambridge University collaborates with local communities across diverse areas by promoting educational opportunities, supporting career growth through apprenticeships, leading healthcare initiatives like the Cambridge Children’s Hospital, enhancing patient care and outcomes via health partnerships and research programs, engaging the public culturally through art events and festivals, and fostering placemaking through accessible transportation services and annual events that celebrate the University’s heritage. Princeton University’s commitment to community engagement, rooted in its mission of “service to the nation and humanity,” is realized through programs like the Pace Center for Civic Engagement, which instils a culture of meaningful service from students' first days on campus, as well as opportunities such as Community Action and the Novogratz Bridge Year Program for local and global service. The university further supports community needs through the Program for Community-Engaged Scholarship, which connects students with nonprofits, offers paid internships through PICS and LENS, fosters faculty and alumni involvement in initiatives like AlumniCorps, and hosts the Tiger Challenge, where students and community partners collaborate to address societal issues.

UCA's campus in Naryn, Kyrgyzstan.

UCA's campus in Naryn, Kyrgyzstan.

PART II

The role of universities in fostering urban resilience is becoming a promising new dimension. Oxford University is crucial in advancing urban resilience through interdisciplinary research, global collaborations, and educational initiatives. The Oxford Network for the Future of Cities, housed within the Institute for Science, Innovation, and Society, examines how cities adapt to pressing social, economic, and environmental challenges, particularly climate change and rapid urbanisation. The Environmental Change Institute conducts extensive research on climate risks affecting urban areas, such as rising sea levels and extreme weather, informing policies that enhance sustainability and infrastructure resilience. Meanwhile, the Oxford Martin School focuses on sustainable urban development and disaster risk management, exploring strategies to mitigate economic shocks, environmental stress, and social inequalities. Oxford collaborates with the Global Centre on Adaptation to accelerate climate adaptation efforts, integrating nature-based solutions and infrastructure improvements into urban planning. Complementing its research and policy contributions, Oxford provides educational programs in urban studies, planning, and sustainability, equipping future leaders with the skills to tackle worldwide urban resilience challenges.

Oxford’s case reflects a broader shift in academia, where universities are increasingly recognised as hubs of research and education and as key institutions in fostering urban resilience. At the beginning of the XXI century, scholars have widened their scope from focusing on technology transfer and commercialisation to investigating universities' role as anchors of resilience-building capacity, shaping the human, intellectual, and social capital essential for sustainable urban growth (Florida, 1999). Wolman et al. (2017) examined the relationship between urban economic resilience and various contributing factors, including the presence of research universities. The econometric analysis of 361 U.S. metropolitan areas from 1970 to 2014 found that each additional research university doubles a city’s likelihood of recovering from an economic shock within a given year. Faoziyah (2022) argued that university-driven community empowerment fosters long-term self-reliance, reducing dependency on government aid. Creswell’s (2009) empirical study highlights that the absence of university involvement often undermines the effectiveness of government-run empowerment programs because universities provide expertise, training, and social engagement, thereby strengthening poverty alleviation strategies and enhancing community resilience to economic shocks.

Universities' role could be especially valuable in strengthening the resilience of small depriving towns, where economic decline and demographic shifts necessitate innovative, knowledge-driven adaptation strategies. The study by Ljubenović et al. (2020) stressed the importance of innovative governance, local cooperation, and strategic use of endogenous resources to create viable long-term development alternatives in small post-socialist shrinking towns, particularly in Eastern and Central Europe. They examined how towns experiencing economic decline, depopulation, and urban shrinkage have adapted by leveraging local resources and social capital. The main findings highlight that resilience in small towns is not merely about returning to a previous state but involves transformation through adaptive strategies. The case studies revealed that towns adopting creative strategy—such as cultural tourism, community-driven urban renewal, and ecological sustainability—could establish new development paths. These strategies leveraged local cultural assets, community engagement, and sustainable energy projects to mitigate population decline and economic stagnation.

Collaboration between local governments and universities is crucial in enhancing urban resilience by integrating risk-informed planning into urban development strategies. Universities serve as knowledge hubs, researching climate adaptation, disaster risk reduction, and resilient infrastructure, which local governments can leverage for evidence-based policymaking. Municipalities can develop risk-sensitive urban plans by incorporating academic expertise informed by the latest research and best practices. Additionally, universities contribute to participatory urban planning efforts, ensuring that vulnerable populations are considered and that resilience strategies align with equitable and sustainable development goals. The University of Southampton, through projects like PREFUS and DECCMA, has contributed to understanding the resilience of rice-dependent communities by using remote sensing and socio-economic data to predict storm impacts and support adaptation planning. The PREFUS project identified areas where rice croplands are more resilient to storms, enabling better agricultural planning to protect livelihoods and food security. Meanwhile, the DECCMA project, in collaboration with UNESCO, evaluated community resilience in the Mahanadi delta, providing empirical evidence and operational frameworks for disaster risk reduction.

Following the devastating 1999 Marmara earthquakes, Istanbul faced an urgent need to assess and mitigate seismic risks. Universities were critical in earthquake risk assessment, vulnerability analysis, and preparedness planning, collaborating with government institutions and international organisations. Boğaziçi University, Istanbul University and Istanbul Technical University, in partnership with the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality and the Japan International Cooperation Agency, conducted detailed seismic hazard and structural vulnerability assessments. The studies identified that many of Istanbul’s buildings lacked earthquake-resistant design, putting thousands of lives at risk. Utilising advanced probabilistic and deterministic models, researchers from Boğaziçi University, alongside experts from the American Red Cross and the United States Geological Survey, projected earthquake probabilities and estimated casualties based on various risk scenarios. Additionally, universities supported the development of the Istanbul Earthquake Master Plan, an initiative led by Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality in collaboration with four Turkish universities, to create strategies for urban retrofitting, emergency response, and public awareness campaigns. Through these efforts, academic institutions contributed to evidence-based policymaking, capacity-building, and risk mitigation strategies, ensuring that Istanbul's resilience to future earthquakes is rooted in scientific knowledge and risk-informed urban planning.

Universities have started to play a critical role in equipping local decision-makers with GIS-based decision-support systems, leveraging remote sensing and hazard mapping to enhance early warning systems and strengthen disaster mitigation efforts. Peking University applies GIS technologies in China’s rapid urbanisation projects, improving disaster response frameworks. Grenoble Alpes University focuses on Alpine climate risks. The University of Oxford researchers investigate flood risk modelling through its Environmental Change Institute, helping cities develop proactive mitigation strategies. Stanford University’s Urban Resilience Initiative uses GIS-based modelling to analyse seismic risks in California, providing data for emergency response planning. MIT’s Urban Risk Lab develops digital tools for mapping flood-prone areas and designing predictive analytics for disaster management. Harvard University’s Center for Geographic Analysis integrates GIS applications for urban heat mapping and flood resilience planning in Boston. In collaboration with the U.S. Department of Energy’s Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, Princeton University has developed AI-driven flood prediction models for storm preparedness. Caltech’s Seismological Laboratory enhances earthquake resilience through real-time ground motion monitoring and the ShakeAlert system. Universities are at the forefront of advancing urban resilience by providing cutting-edge GIS-based tools and research that enable local decision-makers to better understand and mitigate risks, ultimately fostering more adaptive and sustainable urban environments.

GIS-based decision-support systems have become essential disaster preparedness and response tools, enabling more effective risk assessment and crisis management. Johnson (2003) developed a GIS Emergency Management System (GEMS) at the University of Redlands to enhance evacuation planning based on population density, identifying high-risk areas such as lecture halls and dormitories to optimise emergency response. The study emphasises the flexibility of GIS-based solutions, suggesting that similar applications could support emergency preparedness efforts in other communities, universities, or disaster-prone areas. Researchers at the University of Turin’s GeoSITLab developed and piloted SRG2, a mobile GIS application, to support early-warning and damage-assessment efforts for Hurricane Mitch, the Zambezi flood, landslides in Italy’s Aosta Valley, and seismic hazards in the NW Alps (Giardino et al., 2012). By coupling remote-sensing analytics with field training for local responders, the university demonstrated how academic innovation can directly strengthen multi-hazard preparedness and humanitarian relief. At the University of Turin’s GeoSITLab, developed and piloted SRG2 (stands for “Support to Geological / Geomorphological Surveys”), a mobile GIS tool, to support early-warning and damage-assessment efforts for Hurricane Mitch and Zambezi Flood, landslide mapping in Italy’s Aosta Valley, and seismic risk analysis in the NW Alps. By coupling remote-sensing analytics with field training for local responders, the university demonstrated how academic innovation can directly strengthen multi-hazard preparedness and humanitarian relief.

Universities are becoming key drivers of disaster risk reduction (DRR) by advancing scientific research, developing innovative technologies, and informing policy decisions. Izumi et al. (2019) investigated how science and technology can enhance DRR strategies and surveyed academia, government, NGOs, and the private sector to assess which DRR innovations are most impactful. The study found that community-based DRR emerged as the most favoured innovation, underscoring the significance of local participation and bottom-up approaches in disaster resilience. The research highlights that universities play a central role in DRR by generating research, developing new technologies, and shaping evidence-based policies. However, their impact remains limited unless scientific knowledge is effectively communicated and co-produced to influence decision-making. Therefore, strengthening collaboration between universities and local stakeholders is essential to translating scientific advancements into practical, community-driven resilience strategies.

International experience demonstrates that universities can play a transformative role in strengthening the resilience of their hosting cities and towns. However, university transformation is only successful when other local institutions are capable of collaborating and evolving alongside the university. Even the most well-equipped universities may struggle to drive meaningful change alone if there is a lack of adequate commitment, partnership and engagement from local community partners.

The capacity of a region to effectively absorb and utilise knowledge generated by universities plays a crucial role in shaping its economic resilience and long-term growth. Florida (1999, p.71) emphasised that the region’s ability to absorb and utilise university-generated knowledge, or “regional absorptive capacity”, is critical. Collaborative initiatives involving universities, local governments, and private industry can increase such capacity and amplify the impact of university-generated knowledge on economic resilience. Seattle’s transition into a global tech hub, driven by Microsoft and supported by local universities, exemplifies how such synergy enables regions to recover rapidly from downturns (Wolman et al., 2017, p. 116). These examples underscore the vital role of collaboration with local governments and private industry in strengthening the absorptive capacity of a town or region.

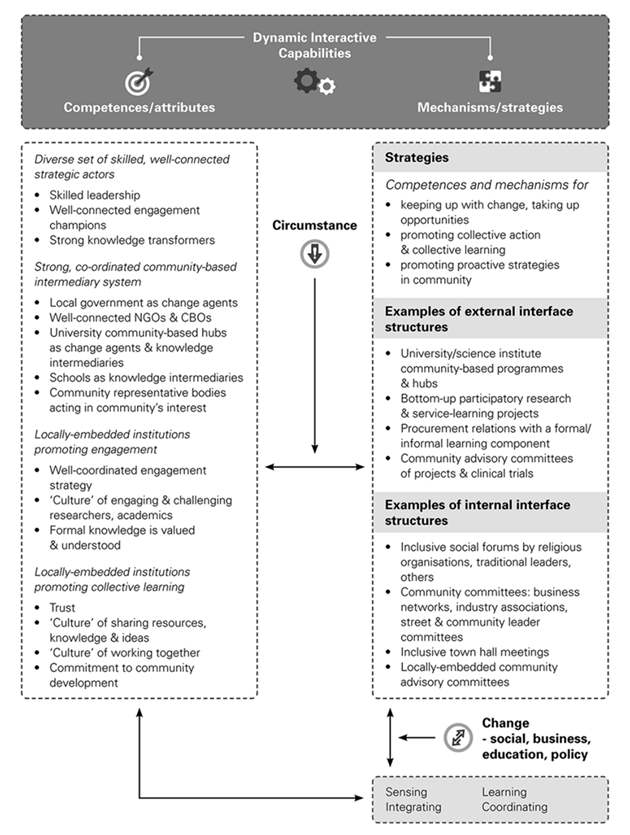

Existing research often emphasises the university's contributions to community engagements but overlooks the reciprocal capabilities communities require to participate in the co-production of knowledge and development outcomes successfully. Drawing from strategic management and innovation systems literature, they introduced a model that explores how communities can build capabilities to utilise university knowledge for their development needs, emphasising the mutual value of engagement for both universities and communities (Petersen et al., 2022). By introducing the concept of “dynamic interactive capabilities” for communities, the authors expand the framework traditionally applied to firms and universities, highlighting the need for a co-evolved, mutually beneficial approach to university-community partnerships (Figure 1). The university's transformational power grows when universities and community partners can reflect, adapt, and reshape their intentions and actions beyond established institutional settings and technologies, with agency distributed through the newly created structures (Garud et al., 2007).

Figure 1. Community dynamic interactive capabilities framework. Source: Petersen et al., 2022, p. 897.

As shown in Figure 1, resource-poor communities and universities can create transformative partnerships when their distinct knowledge assets are deliberately aligned. Communities hold tacit “know-who” and market-specific “know-what,” while universities contribute scientific “know-why.” Effective engagement emerges when gaps are bridged through mentoring, incubation, and participatory projects. Four actor roles drive this process: skilled leaders who mobilise networks, community engagement champions who seize opportunities, NGOs/CBOs that translate research into practice, and intermediaries that coordinate actors - though intermediaries can also inhibit collaboration if motivated by politics. Institutional factors (local norms, trust, and rules) either support or block knowledge sharing, making a coordinated engagement strategy—ideally led by a neutral public intermediary—essential. Internal forums and town-hall meetings enable collective sense-making; external structures such as university hubs, service-learning, local procurement links, and community advisory committees provide repeated interactions that build social capital and circulate “know-how.” Alignment between university practices and local institutions is thus the critical pre-condition for resilient, mutually beneficial partnerships.

Strengthening urban resilience requires innovative research and capacity change within local institutions to implement resilience strategies effectively. In this context, in partnership with local governments, universities offer joint training programs, certification courses, and continuing education initiatives to equip municipal officials, urban planners, and construction professionals with risk-sensitive development and retrofitting techniques. This ensures that building codes and climate-responsive regulations are effectively implemented and enforced. By supporting local governments, certified NGOs, and professional associations, universities play a vital role in strengthening urban resilience through knowledge transfer, skill development, and technical expertise, fostering long-term disaster mitigation and sustainable urban growth.

Cornell University (USA), the Institute for Advanced Studies of the University of Pavia (Italy), and the German Research Centre for Geosciences have contributed by developing risk assessment tools, providing technical expertise, and conducting resilience measurement studies to better understand community vulnerabilities in Chile, Ecuador, Peru, and Uruguay. Universities have also facilitated training programs for local stakeholders, including government authorities, to enhance their ability to implement disaster risk reduction methods. Moreover, they have promoted regional cooperation by building academic and professional networks, ensuring that knowledge and best practices in disaster resilience are shared across borders. By leveraging scientific research and advanced methodologies, universities have empowered communities with data-driven decision-making tools to reduce disaster risks and adapt to changing environmental conditions.

Universities and research organisations have also played a key role in strengthening disaster resilience in Batticaloa, Sri Lanka, by providing research support, training programs, and technical expertise to local disaster management efforts. Following the 2004 tsunami, Sri Lanka established the Disaster Management Centre and the District Disaster Management Coordinating Unit, which collaborates with universities to conduct workshops and training events for local officials, emergency responders, and community members. Universities have contributed by developing disaster management curricula, supporting early warning systems, and conducting risk assessments that help inform district and village-level disaster management plans. Their research has also supported livelihood development programs and community-led resilience initiatives, ensuring that disaster response strategies are tailored to local needs. Through partnerships with government agencies such as the National Building Research Organization and the Meteorological Department, universities have helped integrate scientific data into practical disaster mitigation policies. Universities are enhancing local preparedness, response coordination, and long-term resilience-building efforts in Batticaloa by fostering capacity-building and knowledge dissemination.

By fostering collaboration between academia, policymakers, and industry, universities help develop urban infrastructure to a new “critical” level, ensuring it is more adaptive, inclusive, resilient and sustainable. Critical infrastructure has become a focal point in research, policy, and political discourse due to growing concerns about its vulnerability to various threats, including the risk of terrorist attacks, disruptions caused by natural and human-induced disasters, and the increasing recognition of infrastructure interdependencies within complex urban systems. Steele et al. (2017) argue that critical infrastructure integrates human and environmental considerations and does not solely focus on infrastructure as a physical or economic asset. For example, in cities like Melbourne, water infrastructure serves multiple functions—ensuring access to clean drinking water for all communities, maintaining ecological flows in rivers and wetlands, and integrating Indigenous water rights and management practices. The definition of water infrastructure as “critical” in this case is limited to economic or security concerns but considers its role in human well-being, climate resilience, and environmental protection.

As infrastructure systems face increasing environmental, social, and technological pressures, university-led research and innovation play a key role in shaping policies and solutions that transcend traditional economic and security concerns. Universities actively participate in climate adaptation, contributing through innovations in infrastructure monitoring, policy guidance on climate resilience, and advancements in renewable energy integration, strengthening urban sustainability and energy security. The University of Cambridge’s Centre for Smart Infrastructure develops sensor-based monitoring systems for ageing urban infrastructure. Imperial College London’s Grantham Institute advises the UK government on infrastructure policies addressing climate adaptation. The University of Oxford collaborates with UK policymakers on adaptive infrastructure for climate variability and energy grid resilience. Princeton University’s Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment studies the integration of renewable energy into urban grids.

Universities integrate research and collaborations in applying AI, sustainable mobility, and disaster-resistant technologies to enhance energy grids, transportation systems, and built environment resilience, strengthening cities against climate and seismic risks. MIT’s Sustainable Urbanization Lab works on AI-driven smart city infrastructure, focusing on resilient energy grids and transportation efficiency. Tsinghua University supports China’s smart city projects, integrating AI into urban transport systems. The University of Toronto collaborates with municipal authorities to improve Toronto’s transit resilience. The Technical University of Munich leads sustainable mobility and resilient transport network research. Stanford University partners with the City of San Francisco to enhance transportation networks and earthquake-resistant buildings. ETH Zurich’s Future Cities Laboratory designs green and resilient building technologies.[1] The University of Tokyo develops earthquake-proof housing prototypes.

Universities play a crucial role in providing accessible green spaces, and the study highlights the broader implications of campus environments on community health. The study by Lee at el. (2024) examined the relationship between green infrastructure and community health in three university towns in Texas, focusing on how campus green spaces influence campus users' physical and mental well-being (visitors to campus). The researchers used spatial error models, integrating data from SafeGraph mobility records, Landsat 8 satellite imagery, and CDC health status data to analyse the impact of green infrastructure on campus users' health. The findings suggest that green infrastructure significantly benefits mental and physical health. Increasing tree canopy coverage could be an effective strategy to enhance well-being, contributing to the public health of town residents and students.

Concept of university town

Most interviewers understand the concept of a university town as a dynamic and multifaceted partnership between an academic institution and its surrounding community. Across all responses, university town development is consistently described as:

- A partnership between the university and the surrounding community — most emphasise mutual benefit, shared growth, and co-creation.

- Economically and culturally transformative — development is framed as a driver of local economic vitality, a hub for cultural exchange, and a space for education-led regeneration.

- Strongly tied to place — there’s repeated mention of the mountain community context and the unique geographical and cultural setting.

A clear consensus emerges that university town development is not merely the presence of a university in each location, but the creation of a mutually beneficial ecosystem where education, research, and local life intersect. As one contributor noted: ‘UCA has positioned itself as a catalyst for urban and rural regeneration’. Another stressed the importance of connection: ‘The university should not become isolated and alienated from the community’. All agree that: 'University town development means… people should have a sense of belonging to the community where they live and work'. The framing of the development of a university town as an ongoing, strategic process rather than a one-time project requires the UCA management to strategically focus on strengthening the University Town Development division's expert capacity to create and sustain mutually beneficial partnerships between academics and the town community.

A recurring theme is the transformative potential of partnerships between universities and the town community. Participants consistently emphasise the mutual relationship, mentioning that the university serves as both an economic driver and a cultural catalyst. For some, the university town is seen as a hub that stimulates local businesses, creates employment opportunities, and attracts investment, placing the most significant importance on economic development. Others stress cultural enrichment, seeing the university town as a space for diversity, creativity, and community life. Only a smaller number mentioned primary focus on education and research, presenting the town as an extension of the academic mission. This signals the current gap in how the town could benefit from increased access to knowledge, research, and training, as well as how the university may be turned into a living laboratory for applied learning and community engagement.

References to mountain communities highlight the role of place in shaping development priorities. Here, university town development encompasses not only economic growth but also environmental stewardship, land use planning, and preservation of local traditions. Some definitions focus on specific, tangible activities—such as sustainable agriculture or infrastructure improvements—while others adopt a broader, more conceptual framing, describing the town as a shared social and intellectual space. Whether viewed through an economic, cultural, environmental or educational lens, the UCA staff's interpretation of the concept of university town reflects a deep belief in the potential of higher education to shape not only minds but also the places and futures of town residents. The data present the university town as a place of intentional integration, where the boundaries between academic and community life are blurred in pursuit of shared progress in strengthening mountain towns’ economic resilience.

The perception of the university’s impact is diverse, including both tangible and intangible changes, reflecting several key areas of town development:

- Investment in urban infrastructure

- Knowledge extension by providing educational opportunities

- Research for local development

- Students’ engagement

- Community engagement

From the moment the remote mountain towns of Khorog, Naryn, and Tekeli were selected as host locations for an international university, the trajectory of their development began to shift. The construction of facilities for the SPCE schools and UCA campuses marked the first significant investment in brand-new, high-quality urban infrastructure that meets high international standards. Interviewers consistently described the university’s campus and facilities as a showcase of excellence, as it sets a new benchmark for design, quality, and ambition in the town. The university’s investments in urban infrastructure were followed by improvements to public parks, pedestrian areas, and shared urban spaces, reshaping the town’s safety, accessibility, and aesthetic appeal. Lighting upgrades and street renovations enhanced mobility, safety, and the overall appearance of the town, making it more welcoming for both residents, students and town visitors. Investments have included large-scale tree planting and the creation of green spaces. As one participant recounted: ‘We planted 2,100 trees around the campus… now this place has become green and pleasant’. These visible town transformations driven by the UCA investments in urban infrastructure attracted attention from other development aid agencies and national governments, which began directing their development funding to these towns.

Most respondents state that the university’s influence on education refers to the SPCE’s role in expanding access to high-quality learning, with programs tailored to local needs. As one staff member explained, “We developed over 600 different types of courses, tailored to the needs of the community”. A participant reflected on the results: “People started to remain in the community and not move away, because they saw opportunities here.” The university has supported local schools: “We worked with local schools… held competitions, invited students to visit our campus, and showed them what’s possible.” A faculty member proudly stated, “We have established geology laboratories in Khorog… focused on geology, hydrology, IT and economics”, aligning academic resources with regional development priorities. Over time, these capacity-building efforts have expanded beyond residents and students to include local decision-makers such as civil servants. Initiatives like the NURP illustrate how UCA’s expertise can directly contribute to better urban management by supplying municipal leaders with modern tools such as GIS mapping, evidence-based and strategic planning. However, respondents noted UCA could further increase the capacity of existing small businesses to grow, diversify, and strengthen the local economy. There is a need to find better paths for guiding UCA graduates into local leadership positions, ensuring a pipeline of skilled professionals in town planning, infrastructure development, and public administration.

Some participants noted that UCA has recently begun to place more emphasis on research with direct local impact and to involve community members in its cultural and social activities. Cultural events, workshops, and public lectures have brought together residents, faculty, and students, fostered social cohesion and offered spaces for dialogue and exchange. For many, these experiences create a stronger sense of identity and belonging. One participant reflected on the practical focus of research: “We have some brilliant academics… they’re also deeply connected to solving the problems of the region.” Examples of ongoing studies with local value around agriculture range from improving crop yields to managing natural resources. Still, more should be done to ensure that the created knowledge is translated into practice to benefit town development. Interviewees stressed that while participation in events is valuable, interaction between residents and the university community could be more collaborative and sustained. Rather than only inviting residents to attend cultural programs or public talks, there is an opportunity to involve them from the earliest stages — jointly planning, designing, and implementing both research initiatives and community projects. A significant gap remains in fully harnessing the potential of research to address the most pressing local development challenges. The university’s research could be more localised, tackling local development issues such as environmental management and economic diversification.

Many respondents highlight the way the university equips students with both hard and soft skills relevant to regional needs. Capacity-building investments — such as improved curricula and better-trained faculty — are seen as essential to producing capable graduates. Exchange programs and campus events foster intercultural understanding and open-mindedness. As one person noted, “When you hear people wanting access to our resources, you feel proud… it means we have something worth sharing.” Students are active participants in environmental and social initiatives. One example comes from a student-led recycling effort: ‘We hand all of this in for recycling and exchange it for new stationery supplies’. Students engage in research that directly addresses local issues, fulfilling the institution’s vision as a “research university… [where] students are engaged in inquiry from early on”. However, some respondents point out gaps in student readiness: “They don’t think they have got enough research experience — this needs to start earlier.” While the university’s engagement model is strong, some participants expressed concern that students still lack early exposure to research and practical work. Strengthening these pathways requires planning specific capacity building and students’ engagement to increase their inputs in shaping the future of town communities.

The university’s stakeholder engagement extends beyond town borders. As one administrator explained: ‘We engaged with public universities in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Pakistan and Afghanistan to strengthen higher education in these mountain-based institutions, to ensure that such educational development also contributes to the socio-economic advancement of the surrounding mountain communities.’ Trust-building emerges as a recurring theme. Partnerships with municipal authorities and community leaders are described as increasingly strong. However, participants also identified areas for improvement, particularly in follow-up and sustained engagement. One interviewee suggested: ‘We need to… hold those meetings through which we strengthen our coordination and accountability.’ As one participant described: ‘We work closely with local self-government… giving them a role in decision-making and implementation.’ Several participants emphasised the importance of stakeholders contributing resources — whether land, infrastructure, or expertise — to reinforce a sense of joint responsibility: ‘We need close collaboration with local authorities… it creates a sense of ownership when they invest as well.’ This can be summed up in a remark: ‘We are always open to cooperation… but no one should think it will happen without mutual benefit.’ The interviews portray stakeholder engagement as a cornerstone of university town development, requiring a deliberate effort to foster more horizontal collaboration. This involves engaging municipal authorities, local entrepreneurs, educators, and civil society as equal partners, making the town development process more inclusive and adaptive.

Interviews reveal a shared vision on the value of the university as a knowledge institution to shape town residents' vision, lifestyle, and behaviour. One respondent summed this up: ‘There’s a life, an energy that comes with establishing a university in a small town — it changes how people think about their future.’ There is an expectation that the university will continue to lead in attracting investment and resources for urban development. A participant advised: ‘Start with some projects… which will bring resources into the town and demonstrate the growth potential.’ Respondents emphasised the importance of aligning UCA’s development agenda with local development aspirations, highlighting the need for collaboration and a shared vision to sustain progress. A few participants stressed that the transformation should start early, with investment in educational pathways that begin well before university. As one said, ‘I would advise starting with kindergartens… to show that education is a value.’ This reflects a long-term approach where the entire local education ecosystem aligns with the university’s presence. One respondent envisioned: ‘In 10–15 years, Naryn could become like a US university town where the university shapes the identity of the town.’ This includes creating spaces and events that make the university a central part of everyday life for residents and visitors.

The most comprehensive visions combine education, community services, and social activities into an integrated model. As one participant summarised: ‘Integrated education-service-community development is the way to create a real university town.’ This means that learning, living, and leisure are seamlessly interconnected, enhancing both the student and resident experience. A strong emphasis was placed on designing towns that encourage community interaction and shared experiences. As one participant described, “Green spaces… people come together, discuss, share ideas — this is what makes a university town vibrant.” Such spaces are seen as critical to building both a welcoming environment and a sense of intellectual and cultural exchange. The vision also incorporates economic development, with universities acting as hubs for tourism and business. One participant recalled: ‘There was a plan for touristic infrastructure… to make the town more attractive to visitors and students alike.’ Achieving envisioned transformation requires careful planning, investment in both physical and social infrastructure, and an ongoing commitment to aligning university and community priorities.

The interviews reveal that resilience planning is increasingly recognised as a critical component of the university’s role in strengthening hosting towns. Several respondents emphasised the importance of resilient infrastructure. One participant noted with pride: ‘Our SPCE building… models of that are being replicated for future construction to withstand natural disasters.’ This emphasis on structural safety not only protects students and staff but also sets a standard for the wider community. As one suggested: ‘It should not be that difficult… to get engagement from our researchers in forecasting and mitigation work.’ There is a belief that UCA could emulate global best practices, learning from institutions that lead in disaster preparedness. As one participant put it: ‘We must work more closely with emergency response services and learn from best practices like US universities, which lead in disaster preparedness.’ Participants mentioned renewable energy systems, waste management, and eco-friendly practices as part of the preparedness agenda. As one staff member highlighted: ‘We have solar stations… this helps us save energy and be more independent.’ Real-life crises have underscored the urgency of this work: “Heavy rain… about 60 houses were damaged… lack of preparedness made the recovery longer and more costly.” These events serve as reminders that resilience is not only about planning but also about rapid, coordinated action. However, one academic shared a frustration: ‘Sometimes we are not allowed to research certain environmental risks — yet we have the expertise that could help.’ This reflects a need for stronger collaboration between the university, local government, and emergency agencies.

Mission of the University of Central Asia

The University of Central Asia (UCA) was founded in 2000 as a private, not-for-profit, secular university through an International Treaty signed by the Presidents of Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, and His Late Highness the Aga Khan; ratified by their respective parliaments and registered with the United Nations. UCA’s mission is to promote the social and economic development of Central Asia, particularly its mountain communities, by offering an internationally recognised standard of higher education and enabling the peoples of the region to preserve their rich cultural heritage as assets for the future.

- Abdul-Rahman, M. (2022). A community resilience assessment framework for university towns.

- Abdul-Rahman, M., Alade, W., & Anwer, S. (2023). A Composite Resilience Index (CRI) for Developing Resilience and Sustainability in University Towns. Sustainability, 15(4), 3057.

- Breznitz, S. M. (2014). The fountain of knowledge: The role of universities in economic development. Stanford University Press.

- Brundenius, C., Lundvall, B. Å., & Sutz, J. (2009). The role of universities in innovation systems in developing countries: developmental university systems–empirical, analytical and normative perspectives. In Handbook of innovation systems and developing countries. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Darko, R., & Halseth, G. (2023). Mobilizing through local agency to support place-based economic transition: A case study of Tumbler Ridge, BC. The Extractive Industries and Society, 15, 101313.

- Eesley, C. , & Miller, W. F. (2018). Impact: Stanford University’s economic impact via innovation and entrepreneurship. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 14(2), 130–278. https://doi.org/10.1561/0300000074

- Faoziah, S. (2022). The Role of Universities in Increasing Social and Economic Resilience through the Community Empowerment Program in Cirebon City. International Journal of Science and Society (IJSOC), 4(3), 513-541.

- Florida, R. (1999). The role of the university: leveraging talent, not technology.” Issues in Science and Technology 15, no. 4.

- Fritsch, M., & Slavtchev, V. (2007). Universities and innovation in space. Industry and innovation, 14(2), 201-218.

- Garud, R., Hardy, C., and Maguire, S. (2007) ‘Institutional Entrepreneurship as Embedded Agency: An Introduction to the Special Issue’, Organization Studies, 28: 957–69.

- Giardino, M., Perotti, L., Lanfranco, M., & Perrone, G. (2012). GIS and geomatics for disaster management and emergency relief: a proactive response to natural hazards. Applied Geomatics, 4, 33-46.

- Hershberg, E., Nabeshima, K., & Yusuf, S. (2007). Opening the ivory tower to business: University–industry linkages and the development of knowledge-intensive clusters in Asian cities. World development, 35(6), 931-940.

- Iammarino, S., & Marinelli, E. (2015). Education–Job (mis)match and interregional migration: Italian university graduates' transition to work. Regional Studies, 49(5), 866–882

- Izumi, T., Shaw, R., Djalante, R., Ishiwatari, M., & Komino, T. (2019). Disaster risk reduction and innovations. Progress in Disaster Science, 2, 100033.

- Johnson, K. (2003). GIS emergency management for the University of Redlands. In ESRI international user conference.

- Lee, R. J., Xu, Z., Newman, G., Lee, C., Song, Y., Sohn, W., ... & Ding, Y. (2024). Green infrastructure and community health: Exploring the characteristics of campus users in three university towns in Texas. Cities & Health, 1-14.

- Ljubenović, M., Bogdanović-Protić, I., Mitković, P., Igić, M., & Đekić, J. (2020). Building resilience through creative strategies in small post-socialist shrinking towns. ICUP2020, 205.

- Petersen, I. H., Kruss, G., & van Rheede, N. (2022). Strengthening the university third mission through building community capabilities alongside university capabilities. Science and Public Policy, 49(6), 890-904.

- Roberts, E. B., & Eesley, C. (2011). Entrepreneurial impact: The role of MIT. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 7(1–2), 1–149. https://doi.org/10.1561/0300000030

- Steele, W., Hussey, K., & Dovers, S. (2017). What’s critical about critical infrastructure?. Urban Policy and Research, 35(1), 74-86.

- Wolman, H., Wial, H., Clair, T. S., & Hill, E. (2017). Coping with adversity: Regional economic resilience and public policy. Cornell University Press.